This article is an edited extract from K-L’s new book, The No-More-Excuses Guide to Yoga, from the section called Yoga History, Philosophy and Concepts. It’s a huge topic area, but in seven chapters, there is a succinct overview of much of the territory you might come across in yoga class – including Patanjali’s Eight Limbs of Yoga.

by Kara-Leah Grant, author of The No-More-Excuses Guide to Yoga

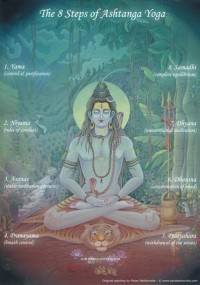

One of the most famous of the yogic texts is The Yoga Sutras. These were either written by, or compiled and edited by a man named Patanjali. He was the first person to codify Yoga in a system – or at least, to do so in a written form. Over the course of 196 sutras or threads, Patanjali expounds on exactly what yoga is and how to attain it or practice it. His method, called Ashtanga Yoga, refers to eight limbs – as in limbs on a tree. These limbs are not necessarily concurrent – you don’t attain limb #1 before moving on to Limb #2. No, each limb develops alongside the others, sometimes concurrently. Much is made of the fact that in these 196 sutras Patanjali only mentions the word ‘asana’ three times, and then in its context as ‘seat’, rather than necessarily ‘posture’. This is the major difference between yoga as we perceive it now (as postures on a yoga mat), and yoga as it is (a state of being you experience).

One of the tools of practicing and attaining yoga – asana – has become synonymous with yoga itself. Very often, we confuse the posture for the yoga.

When you read through Patanajali’s Yoga Sutras, this distinction becomes clear. The 196 sutras are organised into four chapters, called Pada (which also means feet/foot, further extending the idea of eight limbs). These Pada or chapters are called Concentration, Practice, Progression and Liberation. There’s a clear movement from one state of being to another and through to self-realisation- the ultimate aim of yoga. Just to make it clear, Patanajali starts by telling us exactly what yoga is – the cessations of the fluctuations of the mind, or mastery of the activities of the mind (depending on your translation). In chapter 2, Practice, Patanjali states that discrimination is the key for enlightenment and that there are eight rungs or limbs – tools if you will – that lead to discrimination. These eight limbs – literally Ashtanga in Sanskrit, are laid out as follows. The first two are tha Yamas and Niyamas.

Yamas are our own personal ethics or how we behave in the world. There are five of them:

- Ahimsa: Nonviolence

- Satya: Truthfulness

- Asteya: Non-stealing

- Brahmacharya: Being in integrity with your sexual energy

- Aparigraha: Non-covetousness

Niyamas are how we behave toward our self – self-discipline. Again, there are five of them.

- Saucha: Cleanliness

- Santosa (or Samtosha): Contentment

- Tapas: Heat; Spiritual austerities

- Svadhyaya: Study of the sacred scriptures and of one’s self

- Isvara Pranidhana: Surrender to God

These are not so much moral guidelines or ten commandments but behaviours that naturally begin to arise through one’s yoga practice. For example, practicing asana is automatically an act of Svadhyaya or self-study. You are observing yourself in postures, listening to your breath, watching your mind, tuning into the sensations of the body, and learning to stay with whatever arises. This staying with whatever arises is Isvara Pranidhana, or surrender to God. If the word God makes you squirm, think of it instead as surrendering to the moment. It’s fully accepting what is, as it is, right now. Our practice also teaches us nonviolence, in the way we treat our body and approach asana. It teaches Satya – we learn to be truthful about what we’re experiencing, allowing emotion to arise, acknowledging that we need to modify this posture or back out right now, or push ourselves further past our edge.

Over time, as you immerse yourself in yoga, it becomes clear how following the Yamas and Niyamas reduces your suffering in daily life.

It’s like lightening the load and cutting the strings. These guidelines aren’t so much moral directives or commandments, but the natural unfolding tendencies of a yogi in process. The third limb Patanjali mentions is ‘asana’. Now this word means posture, but it also means seat, as in mediation seat – the way one sits for meditation. It’s entirely possible that it’s only in this context that Patanajli was using it. That one learns to find a comfortable seat. This is crucial in yoga practice, because without the ability to sit comfortably for long periods of time it is impossible to do pranayama or meditation (the fourth and fifth limbs). Asana practice also purifies our body – physically, mentally, emotionally and energetically. It makes us healthier, stronger and strengthens our nervous system. This process increases our sensitivity to our internal processes – whether they are mental, emotional, physical or energetic. That’s why Krishnamacharya was able to stop his heart beating at will, or slow down his breath cycle on demand.

Through asana practice, we become far more connected to our bodies and minds, and more comfortable within our bodies.

As already mentioned, the fourth limb in The Yoga Sutras is pranayama. While this word is usually translated as breathing practices, it really refers to one’s ability to work with prana, or life-force. Generally, this is done through breathing exercises because the breath and prana are intimately linked. The fifth, sixth and seventh limb are all aspects of concentration or meditation. Pratyahara is the drawing of one’s attention away from things – such as sounds, smells, sights, tastes or feeling sensations. Instead, one withdraws from the senses into the internal space. Pratyahara teaches us to focus our attention solely on the internal space – which means our thoughts. Dharana now takes that attention on our thoughts and teaches us how to focus it completely – that means our thoughts begin to slow down and perhaps one day even stop. Or at least, pause for a few minutes at a time. The final step in this honing of our awareness – first withdrawing into the internal space then focusing on a single point in that space – is Dhyana, when we learn to sustain that awareness no matter what. This is the uninterrupted flow of concentration. No thought can cause us to waver.

Whereas in Dharana we often use a single point of focus – perhaps our breath, or gazing at a candle, in Dhyana there is nothing but awareness itself. The need to focus that awareness has dissipated and we are simply aware.

Out of this arises the final limb, Samadhi, or Bliss. This is the point of union where our perception of ourselves merges back into the great Consciousness. It’s like we are a drop of water becoming the ocean again. The subject observing the object becomes one and the same. Looking at these eight limbs, it’s clear that the main focus is our attention – where we place it and how we expand it. Everything else serves that purpose. Asana therefore is a tool to teach us awareness and focus, as is pranayama. When you first start to attend yoga classes, you don’t need to know anything about The Yoga Sutras, or the eight limbs. As you progress, you may begin to have questions and at some point, you may want to get yourself a copy of The Yoga Sutras and read it for yourself. Like most of the yogic texts, reading something like The Yoga Sutras takes time and concentration. It’s only short – 196 lines, and very few words – but the depth of those words is endless. If you study the Sutras with a teacher, often you’ll take one couplet and study that for a week, before moving on to the next. It’s easy to revere and bow down before a text like The Yoga Sutras, honoring it as supreme wisdom. Yet it is only one of the many texts that talk about yoga. It’s not that the text might be wrong, but there are other ways you may look at the same concepts – received wisdom is not always ultimate truth, it’s just a pit-stop along the way. Matthew Remski recently released Threads of Yoga which is a remix of The Yoga Sutras. He’s used numerous translations and commentaries to piece together a version of The Yoga Sutras that distills down the essence of Yoga and consciousness within a modern and post-modern context.

If I was picking up a translation of The Yoga Sutras for the first time, I’d be tempted to get Threads of Yoga, as Matthew speaks in a language that is accessible and meaningful to our modern lives, while also adding his own philosophy and comments.

This helps to keep the yoga alive – showing that it’s not something that was created or discovered thousands of years ago and is now held in stone, but something that is forever evolving and changing as we evolve and change. Yet within this evolution and change, The Sutras remain timeless – able to stand and grace us with as much wisdom as they did two thousand years ago. It’s entirely possible that Remski’s modern interpretation and remix will also stand for two thousand years and in millennium from now, students of Yoga will learn about Remski as they do Patanjali. After all, we have Patanjali’s texts, but we don’t know of the man himself. Nor do we know of other great texts that might have been lost to the passages of time. Yes, The Sutras offer wisdom on your yoga journey and they point the way. But they are not the Way.  The No-More-Excuses Guide to Yoga is specifically written to give people a broad and accessible overview of yoga history, philosophy and concepts in a way that makes sense for our modern lives. Pre-orders are now open and you can find out more about the book here.

The No-More-Excuses Guide to Yoga is specifically written to give people a broad and accessible overview of yoga history, philosophy and concepts in a way that makes sense for our modern lives. Pre-orders are now open and you can find out more about the book here.

[…] form of Raja Yoga, touched on in many teacher-trainings, is the eight-limbed path attributed to Sage Patanjali, who compiled the Yoga Sutras. The steps laid out by Patanjali, progressively lead the practitioner through certain attitudes, […]