By Swami Karma Karuna, Anahata Yoga Retreat

What is Resilience?

No matter who we are, the state of the bank balance, or which country we live in; the twists and turns of life, deaths, jobs, relationship stresses, natural disasters, and trauma can affect us all. Change influences each of us differently, altering our biochemistry, thoughts, and emotions. Resilience is our ability to come back to our centre, to rebound from adversity, and to respond to a challenge in a creative way.

The adverse aspects of life are not always enjoyable, yet we have the capacity to increase our ability to manage them through Yogic techniques. Each of us comes to the table of life with a different ability to face the challenges, based on our inner resources, upbringing, education, culture, and so on. This is why two people facing the same situation may handle it in a very different way. While we cannot control everything that occurs, we can learn to better navigate life and empower ourselves with conscious action and thought. Like going to the gym and building your muscles, resilience is a type of muscle that we need to train ourselves in.

Scientists speak about brain plasticity. The common phrase is ‘neurons that wire together, fire together’. It means that whatever we do, think, or feel regularly, positive or negative, sets up the brain and nervous system to do that more easily the next time. For example, if we learned at a young age to run from adversity, to get angry, or shut down in the face of difficulty, this is usually the pattern we will repeat as an adult. Using yogic tools, we can change our responses and set up positive patterns that will better support us.

Stress and Stress-resistance

The stress response in which the ‘flight, flight, freeze’ arm of the nervous system is stimulated is the body’s natural way of helping us survive and is meant for emergencies. When that threat is gone, the body is supposed to come into the relaxation response, for restoration and recovery. However, in modern times, there are a multitude of daily stressors and often not enough recovery time, which lowers our ability to handle true emergencies.

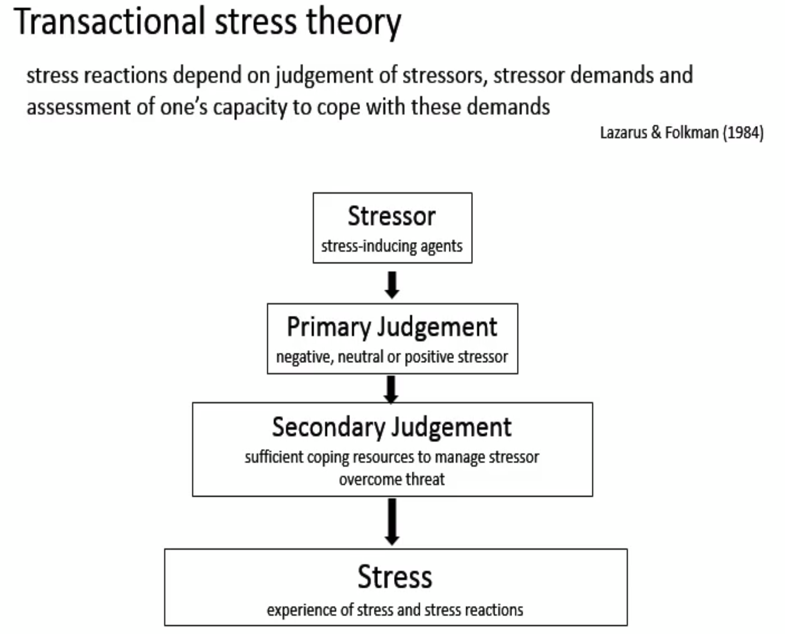

Our bodies’ response to stressors in and of themselves can be a healthy part of life. Some stress, especially if we have a positive relationship with it, can be motivational and an integral part of increasing resilience. However, we need to know how to manage stressful inputs and gradually grow our resilience so that we don’t sweat the small stuff. It is also important to enhance our ability to recover more quickly when we get off balance. It is not about avoiding stress altogether but rather training ourselves to manage it.

Relaxation Response and the Vagus Nerve

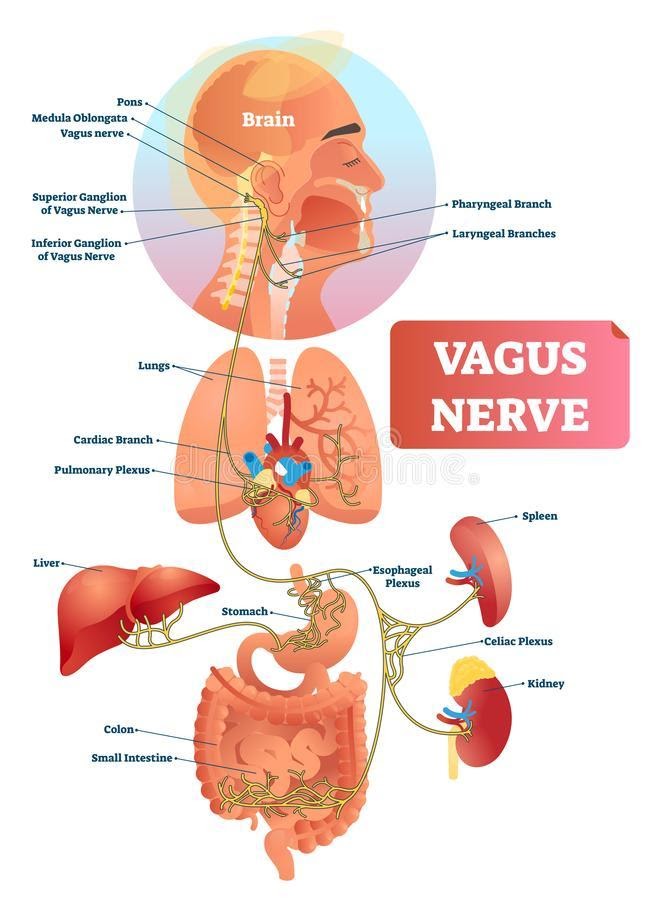

Increasing our vagal tone, which is related to the relaxation response is an important part of this puzzle. The vagus nerve is like an information superhighway carrying an extensive amount of information between every single organ in our chest, abdomen, and detox organs to/from our brain. When stress hormones are initiated, the vagus nerve is the one to tell the body and organs to calm down. It is associated with relax, digest, and repair functions. It is also telling the brain what is going on in the gut and microbiome.

Strengthening the vagal tone is essential in raising resilience because it gives us the ability to relax more quickly after stress. When we are relaxed, we can make choices. When we are in ‘fight and flight’, all the energy is going to survival. This is where yoga and meditation practices become key.

Hatha Yoga and Resilience

Hatha Yoga supports purification, strengthening and flexibility of muscles and joints, toning of organs and glands, balancing of the nervous system, and has many other benefits. When the physical body is operating optimally, there is more resource to draw on in the face of challenges. By stretching and strengthening a little more in a pose but staying present and relaxed, we practice stimulating an area or system and then returning to homeostasis or balance. The more we do this, the faster our recovery time is, which will carry through into our daily lives.

We are also training the mind as it is often resistance or dislike of a posture that stops our ability. There is a difference between extending ourselves to grow our capacities and pain to the point of injury. One should always work within their abilities and listen inwards, however, there is also value in meeting our edge. If we learn to read the signs of our body, it can give us important information. The process may also support the release of stored trauma or unconscious protective armour within the body.

The Breath and Resilience

The breath is another key in building resilience and one of the fastest ways to ignite the relaxation response. It is free, goes wherever you go and the more you do it, the more accessible it is! While an ancient practice, in modern times, diaphragmatic breathing has become a popular tool to tone the vagus nerve. The breath continues without conscious awareness, but it is also within conscious control. There is the capacity to lengthen, manipulate, and alter the breath, therefore providing a direct way to control the physiological responses, emotions, energy, and the mind.

For example, heating practices initially activate the system which help to build our ability to handle heat and stimulation and as the abdomen is used, the practices also have a direct influence on the vagal nerve, which runs through the digestive system, ultimately supporting relaxation. Ujjayi breath influences the vagal tone through the slight constriction of the throat where the vagus nerve also passes through. Bhramari or bee humming or even AUM chanting are all-powerful vagus nerve toners, due to the use of the vocal chords and also the vibration.

Yoga Nidra, Meditation and Resilience

From a yogic perspective, an area of great importance is learning to manage our perceptions of the stressors and gradually train ourselves to be the master of our responses, which involves shifting out of the unconscious ‘fight and flight’ reactions driven by our emotional and primitive areas of the brain to a more considered and conscious approach, where we may experience fear for example, but we can rationalise that it is not a life or death situation.

Mindfulness-based meditation practices such as Antar Mouna and Yoga Nidra train us to become the witness so that we can read the physical signs of our body and mind and know what to do to come back to balance. For example, when we go into a stress response, there are signs in the body like faster breath, higher heart rate, or a repetitive negative thought loop. As we learn to observe changes in the body and mind, we can put in a ‘stress hack’ such as conscious breath, mantra, humming, a calming posture, gratitude, laughing, or a walking meditation.

The practice of Yoga Nidra is also potent for building resilience. Each component within the practice scientifically and systematically balances the autonomic nervous system. Yoga Nidra works by changing the neuronal response to stress, creating somatic conditions that are opposite to those induced by sympathetic ‘fight and flight’ over-activity. The body systems and organs achieve deep, physiological rest, and regenerative mechanisms are activated. (Saraswati, S, 1990, p.91).

The stage of Yoga Nidra that involves awareness of ‘parts of the body’ induces physical relaxation and clears nerve pathways to the brain, relaxing the sensory-motor surface of the brain, the pairing of opposites works on the hypothalamus, limbic system, and amygdala regions all related to unconscious emotional and autonomic experiences. Opposites help to create homeostatic balance and evolve the brain to a point where involuntary functions come under our conscious control. It also decreases blood pressure and circulating stress hormones and changes brain wave patterns.

If we do yogic practices regularly, then when we need them to support us in facing difficulty, they are more accessible. The more we use them, the easier it gets. In this way, we build new neural-circuits and strengthen many important qualities that lead to higher resilience. Over time, we gain more skills, so that when difficulties arise, we have a greater capacity to face them consciously and even actively use the challenges of life to expand, grow, and transform.

References

- Transactional Stress image given by Maarten A. Immink PhD

- Bushan, S., (2001). Yoga Nidra: Its Applications and Advantages. Bihar Yoga Magazine: http://www.yogamag.net/archives/2001/bmar01/yoganid.shtml

- Saraswati, S. (2006). Yoga Nidra. (6th edition). Munger, India: Bihar School of Yoga.

- Saraswati, S. (1990). Yogic Management of Stress. Munger, India: Bihar School of Yoga.

- Saraswati, S. (2008). Asana Pranayama Mudra Bandha (4th ed.). Munger, Bihar: Yoga Publications Trust.

- Serber, E. (2000). Stress Management through Yoga, International Journal of Yoga Therapy, No. 10.

- Sharma, N. (2014). Yoga as an alternative and complementary approach for stress management: a systematic review. Journal of Evidence Based Complementary Alternative Medicine, Jan; 19(1):59-67.

Swami Karma Karuna Saraswati is an engaging, intuitive yoga and meditation teacher, inspirational speaker, writer and yoga therapist with 30 years of experience. She is a Yoga Alliance Education Provider, a senior teacher of Yoga New Zealand and co-founder and director of Anahata Yoga Retreat, New Zealand. Swami Karma Karuna travels throughout the world, leading workshops and retreats, training yoga teachers and offering therapeutic sessions. She is passionate about sharing an authentic and down to earth approach, weaving together the ancient practices with a touch of psychology and brain science aimed at motivating people to live their yoga here and now.

Guides practices, Online Yoga and Resilience course, Yoga Nidra Teacher’s Training and online Therapeutic Session info available at www.anahata-retreat.org.nz

Facebook: Karma Karuna Saraswati

Video Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DSsQ-Xtz5tE

Leave a Reply