by Kara-Leah Grant, Musings from the Mat

Matthew Remski is currently researching asana-related injuries in an attempt to understand what we are actually doing with yoga, and how we can know the value or safety of the postures we practice.

After taking the time to read his first article on the subject – What Are We Actually Doing in Asana – I found myself asking questions about my practice and the pain I sometimes experience in yoga.

In particular, Matthew says:

I would like to explore the liminal space where self-help seems to meet, mysteriously, with self-harm, felt and then symbolized by pain, first considered as a sign of progress, but eventually understood as injury.

I saw myself in that paragraph.

So often when I experience pain during class, I re-frame that pain as evidence that healing is taking place – that my body is opening up and letting go of old patterns and that old injuries are coming to the surface and being released.

But is that true? Or is just another unconscious belief?

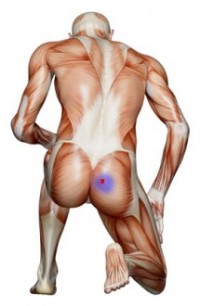

I started yoga already injured, and with limited mobility. I’d already had one spinal fusion, and was on a fast track to a second – I had intense sciatic pain down my right leg, half of my right foot was numb and I was walking with a limp.

Within a year or so of starting yoga – a mixture of Bikram and Vinyasa – my symptoms had largely disappeared, although it took several years to regain full feeling back in my foot. It seemed yoga had healed me, where nothing else had worked.

The last year though, things have been different.

Eighteen months ago, carrying my 2.5 year old on my hip while doing a tour of Anahata Yoga Retreat – up and down uneven tracks – I aggravated my sciatic for the first time in years.

Since then, I’ve done about twenty Bikram Yoga classes and I have been in pain through all of them. I start the class pain free, but by the time we’re into the first posture – Half-Moon sidebends, back bend and forward bend – I’m in agony.

This is in contrast to my home practice where I’ve mostly been pain-free.

In Bikram, I move slowly and with mindfulness, but it appears that the standing pranayama, which includes looking back with the neck, seems to trigger something in my spine. The backbending series at the beginning of the floor series is difficult. Now I’m in serious pain – my back’s seized up and all I want to do is a long, slow child with a gentle adjustment from a teacher to release my spine.

How do I frame this experience? That the yoga is working. That something in my psyche is afraid of letting go and is holding on super-tight creating the pain.

ie. That the pain is my fault for being the way I am – it’s me getting in the way of the yoga working.

How do I justify this pseudo-science belief?

Well… if I have sufficient time in Half-Tortoise Pose and Rabbit Pose, my spine begins to soften and release.

However, setting up for Camel is torture – my back just wants to seize up. At home when I practice, I can effortlessly lift up into Bridge posture – what’s the difference between Camel Pose and Bridge? The shape is the same, but Camel asks us to trust and let go – to bend back and reach back while trusting we’ll be supported.

This is why I’ve rationalised my back pain during Bikram Classes as largely psyche-created.

That, and because by the time the class finished and I take a nice long savasana, perhaps with a few gentle spine-releasing postures, I walk out of class feeling amazing and pain-free.

Yes, after Bikram, within five minutes, all the pain I experience during class completely disappears.

Pain during class. Pain-free after. Must be me holding on right? Me resisting the practice right?

But after reading Matthew’s article, I’m no longer so sure. Maybe I’ve got it wrong. Maybe the practice is causing difficulties in my body and I’m injuring myself by continuing to attend.

Note, while I’m going through the practice, there isn’t consistent pain, or sciatic, or shooting sensations. Rather, there’s a heaviness in my lower back and a sensation of seizing up or contracting. For the entire class I’ll sometimes chant a silent matra of :

‘It’s safe to let go’, ‘It’s safe to let go’, ‘Let go damn it!’ 😉

This past week I’ve done three Bikram classes, and I’m about to go to my fourth. It’s the most asana I’ve done in a long time – my daily home yoga practice is usually far more gentle. I don’t feel like going to this fourth class – I can feel resistance and I don’t want to experience the pain.

I note these two things – I know that usually mat resistance comes before a break-through. As for not experiencing the pain, I’m going to be as gentle as I possibly can during the practice and see if I can avoid going into the pain to start with.

I’m really curious about my experience and about what’s going on.

Can I practice Bikram yoga in such a way that my back doesn’t seize up? What’s causing it to seize up?

I could talk to the Bikram teachers about my experience, but I doubt very much they would be able to shed any light on what I’m experiencing.

And therein lies the crux of modern yoga practice – our teachers, the very people meant to guide us over this intense and fraught terrain of mind/body – sometimes don’t have the training or knowledge of the mind/body to know what’s going on for us.

Compounding this is my recent experience in an Astanga class. I wasn’t asked, nor disclosed any injuries or issues and allowed myself to be adjusted in Marichyasana D. I should’ve realised it was too much for my body and not allowed the teacher to help me into the posture.

As he took me in, I winced in pain – my right hip hurt like hell.

It hurts! I said

I don’t remember his response as he continued to work with me – was it:

That means it’s working. It’s meant to hurt. Breathe through it.

Or somethig similar? I know he didn’t back off, ask me about the area or discontinue with the adjustment and I didn’t stop him.

Again, I rationalised it in my head – this is good, I’m finally breaking through all those hip issues I’ve been having.

Yet post class, my sciatic flared up the worst it’s been in years, and it’s stayed that way for weeks now.

Paradoxically, after a week of Bikram, it’s getting somewhat better again, despite the pain I’m experiencing in class.

And therein lies the conundrum when it comes to pain in yoga class and yoga injuries. Is it good healing pain or bad injury pain? Is there even such a thing as good healing pain? Or is the yoga hurting us and are we rationalising it away?

********

I did that fourth Bikram yoga class, and took time to speak to the teacher beforehand. He was attentive and suggested some minor modifications I could make so as to not aggravate my spine and hip.

I felt supported and listened to. It was a good sign.

In the first breathing exercise, which includes standing in Mountain Pose and tilting the head all the way back to look at the wall behind, I cut myself some serious slack.

Instead of focusing on looking as far back as I could, I allowed myself to just gaze up at the ceiling and stay attuned to my form.

For the first time in a long time, I exited that breath work without any sense of pain or back seizing. So far so good.

I maintained the same softly, softly approach for the rest of class. Unfortunately, the very first asana, Half-Moon, includes standing side bends and a backbend, followed by a forward bend. The side bends put me straight back into agony, despite focusing intensely on form and avoiding depth completely.

The pain persisted for most of the rest of the class. Possibly not as bad, but still there. As always, it was gone within ten minutes of leaving the hot room.

Oh the hot room… post class I came home and did some research into my specific symptoms. Generally, I just say I’ve got “lower back issues”, but given that it’s mostly focused on my right hip, it’s like I’m experiencing something to do with my SI joint on the right side. It’s likely that joint is inflamed.

And serious heat like in a Bikram Class? That’s not going to do my hip any favours…

So maybe it’s not the yoga itself – which does seem to help my body – but the heat of the class causing the in-class flare ups.

My detective work continued when the next day I went to my first Mysore-style Astanga class since the latest sciatic flare up.

First thing I noticed?

Even after sixty minutes plus of yoga, my back hadn’t seized up and I wasn’t in any pain. In fact, I was largely pain free, all the way through class.

Towards the end of countless jump backs (more like inch-backs for me), my lower back was beginning to make it’s presence known in upward dog. It felt more like a lack of strength through the core though than pain per se.

Plus, this time I made sure to tell the teacher when he supported me in standing leg extension that I was experiencing issues in my right hip. He looked down at it.

Give me three sessions, we’ll sort it out.

And he was off to adjust someone else.

Three sessions huh? Tempted to write him off as deluded I was willing to give him the benefit of the doubt.

Post-class, I felt more stiff than I do coming out of a Bikram class, and my body more worked. However, by the next afternoon, my hip felt better than it had in months.

I went back for two more sessions within the week, each time going slightly further in the Astanga sequence, until yesterday when my teacher again took me up to Marichyasana D.

This time I felt far more prepared and open to be adjusted partially into the posture. The sciatic pain I’d been having while sitting and working at the computer had all but disappeared again.

Peter was slow and patient, showing me in detail how to release the hip and soften my torso before even thinking about going anywhere near the bind.

Did it hurt? Yes – but not the kind of pain I experienced last time. This felt like a masseuse working into long-knotted muscles – only in my case, it was the pressure of my left ankle and foot working against my right hip.

I noticed psychologically I wanted to tense up and hold myself against the pressure. I wanted to stop breathing. I wanted to run.

With Peter there, reminding me to soften and breath I allowed myself to feel supported and dropped myself inside the posture. A day later, my sciatic has definitely receded. Peter’s claim at sorting it out within three sessions wasn’t so farfetched.

However, this doesn’t mean that the yoga has healed my injury as such. It means the symptoms have abated.

Did the yoga cause the recent flare-up? Or was it healing the flare-up from 18 months ago? I don’t know.

What I do know is that the entire episode has reminded me how easily we allow ourselves to fall into damaging belief systems, and how vigilant we have to be when it comes to our bodies.

I came to yoga physically fragile, and through persistent and conscious practice I’ve made an enormous difference to my physical well-being. I’m not crippled, nor in a wheelchair, as one person predicted looking at me at 25. Nor have I had the inevitable second back operation another claimed I’d need.

However, if I’m not cautious and totally aware, always paying close attention, I can all too easily overdo it and stress out my spine and hips.

Other students, who came to class physically fit and healthy may paradoxically be worse off than I am. They don’t expect to injure themselves and may not be as conscious or vigilant as they work with teachers or move through classes. Nor are they likely to have the level or awareness or alignment know-how I do.

In casual conversation before teaching a class yesterday afternoon, one of my students mentioned she’d just been at a retreat with a woman who’d come back from India thoroughly disillusioned.

Her Astanga teacher had dislocated her shoulder in an adjustment. I cringed.

This woman was young and her teacher is venerated. Was there a moment in the adjustment when she could have asked him to stop?

If it had been me in the same situation, would I have been any different from her? I’d like to think so, but the reality is, probably not.

Yoga is a complex practice that affects so much more than just our muscles and ligaments.

Its power to affect our nervous system and our psyche is extraordinary. Our own desire to achieve complex postures, or please teachers we admire and look up to, or heal long-standing issues can sometimes override our own common sense.

Ultimately, pain is the body’s feedback system. Injury means we’ve gone too far. It means that something has gone wrong.

The key for all of use, beginners and experienced practitioners alike, is to stay alert and aware during class, always tuning into what’s going on in our body and trusting the signals that it’s giving us. If we don’t, the price we pay can be high.

Subtle beliefs like the one I’ve unearthed in my own psyche – that old injuries surface in class and hurt when they do, and it’s just a part of the healing process – could be doing us more damage than we realise.

Matthew is already well underway with interviewing people about their yoga injuries. He says:

I heard stories of crippling injuries, poor self-regard leading to the failure to establish boundaries, and of course incompetent teaching ranging from the negligent to the invasive to the abusive….

Between these extremes, the subtler ideas and feelings that are the target of this study (so far as I imagine it) began to emerge. Alongside stories of positive growth, subjects told me about asana-related injuries they kept secret, blamed themselves for, and obsessed over as symbols of a kind of original sin.

Subjects told me of how they either internalized the aggressive attitudes of instructors more interested in the presumed rules of practice than its effects, or how they used yoga to reify their pre-existing attitudes of bodily ambivalence.

My story of injury and awareness is only one small wave in the ocean, however Matthew is collecting many stories, and from these stories will pull together common experiences and themes.

It’s an exciting piece of work and I look forward to reading more from him in coming months.

If you have your own story of yoga injury you’d like to share with Matthew, you can email him here. Or to just share with YLB readers, you can also comment down below.

Pain in my practice is never acceptable.

As a yoga teacher who came to yoga through injury, from a car crash in fact. Which gave me lumbar scoliosis and a destabilized sacroiliac joint. I can honestly say that I have been very fortunate in my journey with teachers who never told me to push through. Rather I was encouraged to adopt a no pain is no pain and no pain is good philosophy. In fact this is at the very foundation of the 8 limbs of yoga, ahimsa. Non using violence in my thoughts and actions towards a body I was more than frustrated with. With this I encouraged my body to gently open. Going from years of sleepless nights and agony yoga gave me my body, freedom and life back. So much so that I now teach to share the joy I have learned.

In fact there is sound biological evidence to support this approach. Long slow breath awakens the parasympathetic nervous system which allows the muscles to relax. This cannot happen when we are in pain. The shallow breathing associated with pain instigates the sympathetic nervous system and actually causes tightening of the muscles, in my mind defeating the purpose. It is very humbling to the ego to accept the bodies limitations and find and choose variations that are suitable for your body. Do you reach enlightenment faster by doing the biggest upward facing dog, or are you better served with cobra pose until the back is stronger.

I read this article with sorrow that a person was injured and I really wanted it to be known that there are many approaches to yoga and not all of them are suitable for every body. As a teacher I know from that side that it is impossible to be in another person’s body. I always ask my students to consider themselves as the teacher and me as a facilitator because they know their own bodies best. I also only have one pair of eyes. From a students point of view I am aware of the temptation to keep up with the crowd and assume that the teacher knows best.

But the bottom line is whether yoga heals or hurts is ultimately your choice. After all it is your body – remember you only get One!

“When our best tools become vehicles for attachment” by Leslie Kaminoff: http://yogaanatomy.net/tools-attachment/

Kara-Leah, thank you for sharing your experience with yoga and healing injuries. I am the creator of a style of yoga called YogAlign which is a mindful practice based on attaining innate natural posture rather than trying to perform poses. The human body is not linear and in fact made up of curves and spirals. The shapes of many yoga poses simply do not fit the curves of our structure and doing things like standing head to knee in Bikram is a pose that undermines the very fabric of the structures that hold our joints stable. Stretching is a myth because muscles actually cannot be pulled into a longer position. When a muscle feels tight, it is tense ! Muscles need to relax but first we have to provide the body with upright alignment because tense muscles are a result of misalignment. Temporarily relaxing a muscle does not fix the reason why it got tense or tight to begin with. the body is a global structure where all parts affect the whole.

. 95% of pain in the human body is a result of misalignment and pain is the body’s way of communicating that the position you are in is causing damage and you should not go further. When you get pain from poses, just because it goes away later does not indicate that it did something beneficial. Oftentimes the extreme positions in yoga can cause the stretch receptors to turn off so that you do not get pain so you lose the communication from your body. When you go further and override the stretch receptors, you man actually damage the body by breaking the collagen bonds that make up the ligaments and connective tissue joint support forces. In my book, a yoga pose or position is best practiced with a discerning questioning dialogue between the heart and mind. Does this pose allow me to breathe deeply? would I ever use this body position in real life function? Is my spine being compressed out of its natural curves?

I have not seen you but from what you say, it sounds like you have over-stretched your sciatic nerve and also the ligaments of your sacral joint. You need to do poses that stabilize your hips not open them in order to stop this pain permanently. If you are curious, please check out my site at http://www.yogalign.com

Hey Michaelle,

Thank you for such a long & in-depth comment. I’m not sure if the pain is coming from the poses at all – it seemed to come from just being in the room as such. That’s what made it so interesting. The exact same postures approached outside the room were pain-free. And I don’t know if pain is even the right description either – intense sensations maybe? A heaviness? A contraction? A holding? I don’t know. It’s curious. There is always full breath in all the yoga I practice – breath is my teacher as such, allowing the postures to naturally arise from within, rather than imposing a structure from the outside. Even in Bikram, this is possibly by moving slower and allowing everything to be breath led, letting the alignment arise naturally.

I’m not sure I’ve over-stretched anything simply because my range of movement is not that great at all. It feels more like mental and emotional tensions affecting the muscles and joints. But I don’t know – that’s why I continue to question into my experience and not take anything for granted. I shall take a look at your website – thanks for posting the link.

I’m not sure if there’s ever any easy answers to pain, injuries and yoga. Ultimately, it feels like bringing greater and greater awareness to whatever we do is the key. I’m also ambivalent about the role of pain. When I teach, I make it clear to students that they’re never to go into pain – that pain is the body’s signal to back off, you’ve gone too far. However, that’s because it’s my job to take care of my students. In my own practice, the reality is less black and white. I’m aware of how entangled our bodies and minds are – if I become afraid going into a posture, does that make me tighter and generate a strong sensation in my body that I might interpret as pain, even though it’s not? What happens if I stop there and breathe into that strong sensation, softening around it instead of moving away from it?

So very curious! I’m working on a follow-up to this article as well… as you can see, I’ve got lots to say about it 🙂

KL, You say” Even in Bikram, this is possibly by moving slower and allowing everything to be breath led, letting the alignment arise naturally”

The question is how does doing things like the opening breathing exercise with the neck extended back assist anyone in real life function? I cannot take a deep breath in that pose and since the spine is a kinetic chain, my lumbar spine follows the same collapse as the neck.

There are ligament forces that have a ‘necessary tension’ to keep our neck stabile in neutral upright position. ( Since most people in the western world age by going forward, I consider keeping naturally aligned posture to be in and of itself a deep practice)

This head back breathing pose is very compressive to the posterior cervical spine while over-stretching the anterior forces.

Another pose that does not seem

natural to me is the standing head to knee pose in Bikram. This is simply not a natural or comfortable body position. So how does one find alignment naturally in that position? I am talking about posture alignment not ‘pose’ alignment. At the end of the day, your innate postural alignment forces are way more important than what you do in a yoga pose. How is your posture for your life? I work with many who seriously regret doing yoga poses that unbeknownst to them caused longterm damage to the joint mechanisms. A young woman who did years of intense yoga now in her 30’s expressed her desire to just be able to take a walk without her hips hurting. She used to put her feet behind her head and push her chest to her thighs and is now paying a heavy price in terms of chronic pain.

Standing head to knee pose takes the shock absorbing natural curves out of the spine and flexes it with a load force of about 700 pounds. To get chest to knees, one reverses the lumbar/sacral joint nutation, stretches the posterior longitudinal ligaments in the back spine and to top it off, the advanced version features a locked-out hyperextended knee joint. It looks to me like the ‘perfect storm’ for creating pain and joint problems through repetition of this body position. Forcing the tibia and fibula posterior to the femur is a bad idea and certainly we do not think of people standing with knees locked back in normal life as ‘good posture’. Why and how is this a ‘good pose?” Please explain to me because I just cannot see any reason to do it that will bring a positive outcome.

Even bending over with both knees straight in standing or seated forward bend overrides our natural joint forces. WE are designed to move and that means we have to bend our knees so we can exert force with our legs and gluteals.

Try to walk without bending your knees and then ask yourself why do you think its OK to bend over with the knees straight?

Hamstrings are not tight and they cannot be stretched. They are tense and strained from poor alignment patterns.

Your body has quite possibly become destabilized by performing yoga poses that undermine how your body is held together and how it is designed to move.

The yoga sutras says we need to balance sthira and sukham. Sthira means posture should be steady and strong and sukham translates to comfortable, ease-filled, happy etc. So I suggest you question whether the yoga asanas we do in modern times actually follow those principles. The injuries are a result of putting the body in positions that go against the intelligent design of the human body and it is the right angled straight line poses that are the root of the pain and imbalances. There are no straight lines in nature. Humans are part of nature. Linear and straight does not exist in the human body so I suggest a practice that supports the natural curving forces. Also there is no way one can take a deep breath in a forward bend with the knees straight. I call that pose driving with the brakes on. Can we consider thinking out of the yoga box and get back in touch with the true design of our body with some anatomical common sense? I am here for support if you need it and have even more information at http://www.yogainjuries.com

Hey Michaelle,

This is fascinating stuff… I had to stand up and do the opening breathing exercise to feel into… and I experience it differently from you. I can take a deep breath with ease, and my lumbar spine doesn’t collapse at all, and neither does my neck. Yes, there’s compression, but there’s still a sense of lift out of that rather than compression. However, I’m just going by how the posture feels energetically within my body – I don’t know the anatomy inside out.

I don’t think my body has been destablised as a result of yoga though – I was broken, rigid and in total agony when I came to yoga. I had serious sciatic, constant spasming, my right foot was half numb, I walked with a limp… it’s yoga that has slowly opened and healed this over time. Yes, occasionally I do get the odd flare up of sciatic, but it’s nothing like it was back in the days before I did yoga.

Regardless, I love how you know this all inside out and bring so much passion to the subject. You’ve given me much to think about, and to bring awareness to in my practice.

I’ve got issues with my hip joint and I have to say the majority of people who I’ve met with hip issues via online forums and in person do NOT practice yoga and never have. I think we need to be very careful about blaming yoga for joint damage as there are other factors at play like genetics, age (hip impingement often becomes symptomatic in your 20’s + 30s for example), your weight, sports, poor bio-mechanics, a generally active lifestyle, an inactive lifestyle and sitting too much.

Yoga can do a lot of good things for the joints if practiced mindfully and with care. I am in a lot of pain and my lifestyle is prohibited but I have no regrets about my yoga practice. While I agree yoga was probably a contributing factor to my hip issues I can’t blame it entirely. Yoga was an issue for me because I have have hip FAI and didn’t know I am hyper-mobile until several years after I started practicing. I should have taken more care with my joints on the mat and focused on strength over flexibility. But even if I did, I would probably be in the same place I am now because I was very active and loved kick boxing, mountain biking and spin classes!

Yoga therapy, philosophy and meditation have been an absolute life saver over the years while I’ve dealt with my hip pain which has had me on crutches for months at a time. I’m due for my second surgery this year, and I’m hoping to return to the mat (and classes) as soon as I’m ready. I’ll definitely need to be more mindful, work with modifications to suit my needs and ensure strengthening is a big part of my practice — but hey, Isn’t that what yoga asana should be all about?!

I think the bigger issue at play here is the lack of regulation for yoga teachers in New Zealand to ensure the quality of teaching is at an acceptable standard to maximise student safety. I’ve seen some shockingly unsafe teaching in my city, including a teacher who thought it was a good idea to get the class to do multiple repetitions of urdhva dhanurasana in quick succession without holding of the posture or resting between! Now that IS a perfect storm for injury.

Err… that wasn’t overly well written, I’m overtired and my body is telling me to rest (I’m choosing to ignore it). An interesting topic to write about in the future would be “yoga and pain management” – flipping the yoga injury debate over to explore how yoga can be used to manage and treat chronic pain. Because the reality is that the human body isn’t designed to be perfect forever so we are all going to deal with chronic pain at some stage. Many people come to yoga BECAUSE they are in pain and it is a very effective tool when practiced with care.

Hey Julia,

That’s a great idea – moving away from the idea of having this perfect pain-free body and instead accepting the fact that we will age and decay, and how do we meet ourselves there? I like it 🙂

Julia, You are correct that there are many factors that can lead to hip problems especially FAI or femoral acetabular syndrome. Since we engage our body in various activities all day, it is hard to say exactly how hip destabilizations occur. However if we focus on doing yoga to increase ROM in anatomically functional body positions and keep the spine in its natural curves, we would be creating the balance needed for a pain-free body and stable joints. Many yoga poses that take you into positions that do not simulate real life movement and functions stress the muscles, tendons and ligaments because these tissues can not stretch in an elastic way like a piece of fabric. Many people are basically destabilizing their joints trying to do poses like straight leg forward bends because we are designed to move. You have to bend your knees to do that so stretching with the knees straight it like driving with your brakes on. We have to think globally to help yoga evolve in a way where it will be more effective and cause no injuries. More and more yogis are having SI joint pain, FAI syndromes, and even hip replacements. So people may say that yoga did not cause it but yoga did not prevent it either. A functional movement based yoga practice could in fact be a warranty for your joints to last a lifetime. I think the human body is designed well; we are just doing things that override natural function.

Before 1972, we did not have hip replacement surgeries or FAI surgical procedures to repair torn labrums or remove bone spurs from the neck of the femur caused by compression forces. So I feel that factors such as chair sitting, compartmentalized exercises like keeping the navel drawn in or tail bone down, and bending over with spinal flexion instead of hip flexion and doing intense twists with the lumbar spine flexed are causing repetitive strain to the forces that hold us together. The spinal column should not be flexed as is done in any seated or standing forward bends. Any back doctor will urge people to always take the hips back, bend the knees and keep the spinal column in neutral when leaning over. The posterior ligaments in the spinal column and lumbar/sacral region are damaged because many yoga classes repeatedly require forward bend after forward bend and the spinal column breaks down after repeated practice of this type. Please check out my article at Elephant Journal

called ‘When flexibility becomes a liability” http://www.elephantjournal.com/2013/07/when-flexibility-becomes-a-liability-michaelle-edwards/

I really like how you challenge the thoughts about pain equaling healing. It is so important that we remain mindful and aware during yoga so we can truly identify and work with any kind of pain that may arise.