Embracing darkness means surrendering to stillness, rest & the rhythms of the natural world.

by Lucinda Staniland

I’ve been practicing yoga for eight years, and while I’ve experienced many benefits from a regular practice, deep sleep hasn’t been one of them.

Despite my daily home yoga practice—and the deep relaxation and release that it enables—until recently, a really good night’s sleep was an elusive thing for me.

Let me get this straight; I’ve never been an insomniac. I’ve never experienced the terror of a full blown sleep disorder or extreme sleep deprivation. But I do know what it’s like to feel constantly tired; to always struggle to get to sleep, even when exhausted; to wake several times in the night, and to wake up feeling groggy and gross.

I thought that this was a relatively normal state of affairs. I was wrong. While this condition may be ‘normal’ in our society, it’s certainly not normal, or healthy, for the human body.

Then I discovered something that dramatically changed my experience of sleep and darkness.

As a result, I now sleep deeply, for seven to nine hours a night, and I awaken (on most days!) feeling refreshed and wakeful, ready to get on my yoga mat and begin the day ahead.

I fall asleep quickly, almost instantly. Gone is the anxious inner dialogue that used to take over my bedtime brain: What if I can’t fall asleep tonight? Only five hours left until I have to get up… I know I’m going to feel terrible tomorrow if I don’t get to sleep soon. In its place is a respect and appreciation for the quiet haven of the night, and the deep rest that I find there.

The change that I made is very simple: I ensure that the majority of my evenings are quiet, relaxed and—this is the key—dark.

Yup, darkness, with a particular emphasis on avoiding blue and white light (more on the science of this later). For me that means limiting all artificial light, including time spent watching TV, mucking around on my laptop, or checking Facebook on my smartphone. If I really need to do those things, then I use apps like flux that block the white and blue light rays.

In the evenings, my husband and I light our home with candles, lamps installed with orange or yellow lightbulbs and the pink glow of a Himalayan salt lamp. We also make our bedroom as dark as possible—no blinking lights, no LED alarm displays, no light streaming in from the street lights—just the heavy comfort of the dark.

This makes such a difference to my sleep; I can hardly express my gratitude. Sleeps feels easy now, nourishing and life giving. I’m easily in bed by 9 pm most nights, I fall asleep straight away and naturally wake up again 8 hours later.

So what’s so powerful about darkness?

I discovered the power of darkness concerning sleep when I stumbled across some recent scientific research (via this excellent summary from Chris Kresser, How artificial light is wrecking your sleep, and what to do about it). The research shows that exposure to blue and white light (the kind emitted by your devices and light bulbs) suppresses the body’s melatonin production. This isn’t an issue during the day when your melatonin levels are naturally low, but at night time you need to your melatonin levels to rise. Why? Because melatonin is the handy hormone that makes you fall asleep.

Melatonin production is tied to light exposure: When you get up in the morning and greet the bright light of day your melatonin levels naturally drop, and when darkness comes in the evening melatonin levels shoot up again, sending you off to sleep.

The problem is, now that we have access to bright light 24 hours a day this ancient sleep-regulation mechanism doesn’t work so well anymore. So, what can we do about it?

Well, there are lots of things: amber light bulbs, blue-light-blocking glasses (think orange sunglasses—I haven’t tried these yet but have ordered a pair to try), apps likes flux, minimising screen time and lighting candles are just some of the things you can do to stop artificial light messing with your sleep.

But I’ve come to think that this knowledge is about more than just slapping on some orange glasses and downloading an app; it’s an opportunity for us to do something radical, a call for us to reclaim the quiet beauty of darkness.

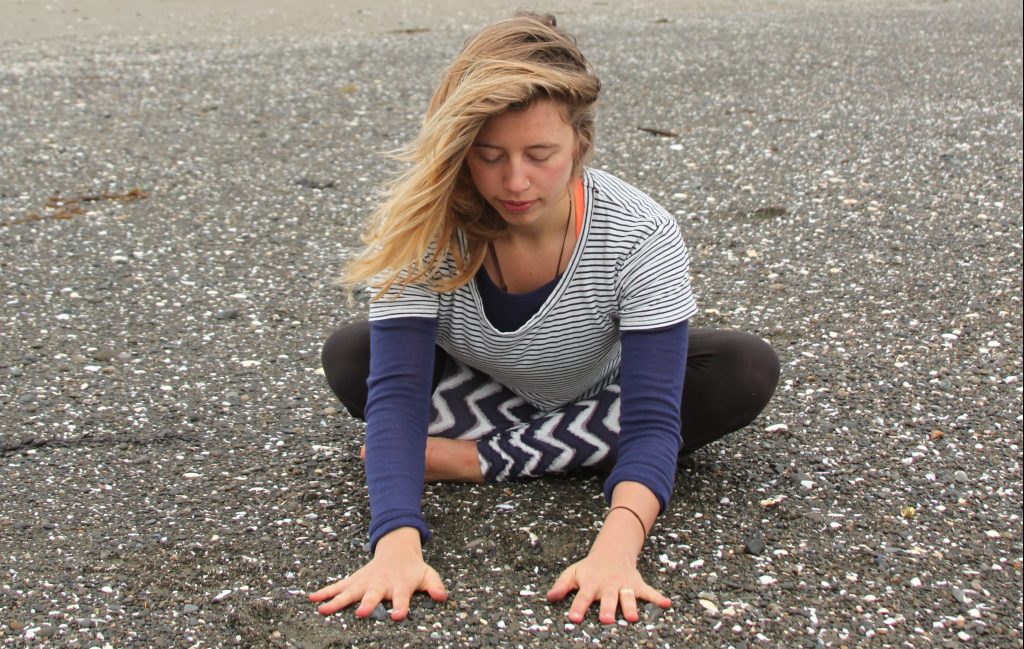

For example, I love practicing yoga in the dark. I usually awaken early, in darkness, and begin my yoga practice in the soft light of dawn, perhaps with a candle or two to light my way.

This practice gives me a sense of being in rhythm with the patterns and cycles of nature. In the same way, going to bed earlier in autumn and winter, when the nights are long, dark and cold, feels deeply right. At this time of year, I do seem to need more rest, while the long light-filled evenings of summer invite play and celebration.

I also genuinely enjoy our dimly-lit evenings at home. Sure, our routine does have its challenges, disadvantages and downsides. It’s certainly not perfect. Life is messy and so is our evening routine. But I’m committed to this way of living because it leads me to a place of profound rest—something that most modern people, myself included, seem to have a deep craving for.

On a deeper level, embracing darkness may also have profound psychological and spiritual impacts.

After all, we’re all a little bit afraid of the dark, and for good reason—the dark is where the unknown lives. We can’t define darkness, we can’t grasp it, and we can’t see into it. To embrace darkness is to embrace stillness and not-knowing. Our culture loves (and rewards) knowing and doing, but not-knowing and resting are much harder concepts of us to grasp and value.

My favourite Irish poet-philosopher, John O’Donohue, is a great advocate of befriending darkness, in ourselves and in the physical world. In his book Anam Cara, he despairs at what he calls the the harsh light of modern consciousness.

“The light of modern consciousness is not gentle or reverent; it lacks graciousness in the presence of mystery; it wants to unriddle and control the unknown. Modern consciousness is similar to the harsh and brilliant white light of a hospital operating theatre. This neon light is too clear and direct to befriend the shadowed world of the soul. It is not hospitable to what is reserved and hidden.” (109)

In a neat parallel with current scientific thought, O’Donohue is a fan of candlelight in the evenings. He says,

“Before electricity, people used candlelight at night. This is ideal light to befriend the darkness… Candlelight perception is the most respectful and appropriate form of light with which to approach the inner world. It does not force our tormented transparency upon the mystery. The glimpse is sufficient” (110)

Slowly, I am learning to befriend darkness. Instead of banishing it from my home I invite it in.

The physical rewards are fantastic—who doesn’t want deep, peaceful sleep and more energy during the day?—and I’m just beginning to uncover some of the deeper and less tangible benefits. Who knows where this journey will take me?

Leave a Reply